On December 18, 2014, President Obama signed the Designer Anabolic Steroid Control Act of 2014 – “DASCA” for short. Several years in the making, DASCA cracked down on the over-the-counter “prohormone” segment of the sports nutrition supplement market and listed 25 steroidal compounds as newly criminalized anabolic steroids.

On December 18, 2014, President Obama signed the Designer Anabolic Steroid Control Act of 2014 – “DASCA” for short. Several years in the making, DASCA cracked down on the over-the-counter “prohormone” segment of the sports nutrition supplement market and listed 25 steroidal compounds as newly criminalized anabolic steroids.

But the lack of any delay in the effective date of the law created a problem. The previous anti-prohormone legislation (2004) gave a 90-day grace period before the law took effect. By failing to include a grace period or delayed effective date in DASCA, the law turned tens of thousands of people into federal drug criminals overnight. For example, the bottle a customer bought in a store on December 17 became a controlled substance the next day – subjecting that consumer to prosecution for federal drug possession. Consumers, manufacturers and retailers who found themselves in possession of these newly illegal products were obviously keen on getting rid of it. But how? Existing law and regulations seemingly provided no lawful mechanism to do so.

So the very next day, on December 19, 2014, I wrote a letter to the Drug Enforcement Administration, which is charged with enforcing DASCA and other federal drug laws. What are people supposed to do? What about mom and pop nutrition stores who still have stock? Or manufacturers or distributors? Or ordinary consumers, who might have recently bought the products in a neighborhood health food store? I was concerned that people might just flush them down the toilet, creating a public health hazard in the water supply. Alter all, these are steroidal chemicals and none of us would want our kids ingesting them inadvertently. I wrote:

The new act has no “grace period,” so that manufacturers, retailers and even consumers are now immediately subject to prosecution for federal drug crimes. I am being contacted by parties from across the country, including mom and pop health food stores, asking what to do with their remaining stock of these prohormone products. I have no answers for them. Existing DEA regulations do not cover this situation. I am not sure if anyone has considered the implications. It seems like there might be a public benefit to having an amnesty/enforcement immunity period for companies that use DEA-licensed disposal firms to destroy their stock (this would not be to allow “sell off” but only for voluntary destruction). If firms believe they will be prosecuted for either DEA or FDA violations if they document responsible disposal, and in the absence of legal guidance or specific regulations, I do not know what they might do. I am concerned that we could have a potential environmental problem unless they receive some type of guidance. Please call me to discuss.

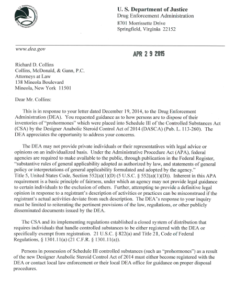

For months, I heard nothing. Then, more than four months later, I received a letter dated April 29, 2015, from the Chief of the Liaison and Policy Section of DEA’s Office of Diversion Control. The long delay somewhat made it a moot point – anyone looking to ditch the products probably already did, one way or another. But I was hoping for a thoughtful consideration of the problem. Well, the letter suggests that people looking to discard the products – which would obviously include consumers – “must either become registered with the DEA or contact local law enforcement or their local DEA office for guidance on proper disposal procedures.” What? Register with DEA to dispose of a bottle of prohormones? Call the local cops? Or call a local DEA field office? Why would a local DEA agent have a better grasp of a national policy problem than the DEA Headquarters? Well, anyway, you can read the letter for yourself.